|

|

|

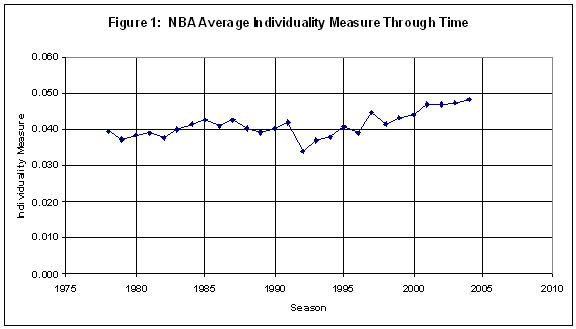

Impacts of Individual Basketball on the NBA by Dean Oliver, 10/30/04 Everyone wants to be The Man, the guy that everyone looks at to make a shot. Itís a badge of honor to be looked at to take a critical last shot, a badge whose honor grew with the success of Michael Jordan, who hit at least 25 game-winning shots in his Hall of Fame career. Those game-winners didnít make MJís legend, but they added a lot to it. They certainly helped add to his salary, his endorsements, and the number of kids wearing his shoes Ė all things that the modern NBA player likes to have more of. But even Jordanís legendary ability to win games on the last possession is overstated. For instance, note that the list of his game-winners is shown at http://www.nba.com/jordan/game_winners.html, but the site doesnít show a single time that he missed a game-winning shot, something that Jordan has admitted to doing quite a few times. People have forgotten those. The Man is remembered for his successes and not the fact that he had so many opportunities to achieve them. Another example of how the myth of The Man has grown without concern to facts is that two of the Bullsí title-winning last second shots were not even taken by Jordan. MJ did make the winning bucket in 1998 to walk away with a title, but John Paxson hit the title-winner against Phoenix in 1993 and Steve Kerr hit the winner against Utah in 1997. Jordan was a very important player to have around when the other guys made their shots, but he didnít need to take the last second shot. That is something that should be mentioned to NBA stars: they donít have to be the guy shooting the last shot to win the title and still be The Man. The culture of wanting to be The Man has led to individual basketball, where one player makes up a big bulk of a teamís offense. This style was not considered a virtue before the success of Jordan. The classic coaching philosophy of balance on offense Ė the kind of balance that the Celtics had as they repeatedly defeated the Wilt Chamberlain-dominated teams of the 1960ís Ė was strived for by most teams up through the 1980ís, with players like Larry Bird and Magic Johnson becoming known as much for their passing as anything else. Since Jordan, coaches havenít openly disputed the philosophy, but they have indirectly dismissed it by proclaiming the need for a Star in order to win. It is now lore among fans that you need a Star to win a title and they complain when their local ballclub doesnít acquire one in the offseason. At the same time all this has been happening, the league that was Fan-tastic in the 1980ís has been losing its luster. Scores have been coming down. Players Ė even "stars" Ė are ridiculed for their lack of fundamentals. No one can hit a mid-range jump shot. Every seven-footer wants to shoot three-point shots rather than a hook shot on the block. The story of how the league got here is a long one (one Iím thinking of putting together under the title "Gunners, Worms, and Steals"), but part of that story is becoming clear as relatively important: individual basketball. Individual basketball has definitely become more prominent in the NBA. I found a way to measure it. And those measurements have shown it rising as offenses have gotten worse. Itís a pretty good correlation. Let me explain. Measuring Individual Basketball A balanced team is one where each of the five guys on the court does about the same amount. Each teammate is about equally likely to shoot or drive or pass or get to the line. Following the terminology laid out in Basketball on Paper, each teammate uses the same number of possessions. Five guys each using the same number of possessions would be 20% apiece. The Dallas Mavericks of 2004, for instance, were a pretty well-balanced team. Dirk Nowitzki used 23% of the teamís possessions. Antoine Walker and Steve Nash both used 22%. Antawn Jamison and Michael Finley were both at 20%. The top two substitutes, Josh Howard and Marquis Daniels, were at 18% and 21%, respectively. Thatís very good balance. An opposing defense didnít know who to guard most closely. And, perhaps because of this, the Mavericks had one of the best offenses in NBA history. On the other extreme in 2004 was Philadelphia, with Allen Iverson using 35% of the teamís possessions, and Minnesota, which had the trio of Kevin Garnett, Sam Cassell, and Latrell Sprewell using 80% of all possessions, leaving guys like Trenton Hassell with 10%. Philadelphia has been like this since Iversonís arrival, whereas Minnesotaís situation was somewhat unusual because they didnít have any scorers beyond their top 3 while Wally Szczerbiak missed so much time. Certainly not Mark Madsen, Trenton Hassell, or Fred Hoiberg. If youíre into the technical details (if youíre not, just skip this paragraph), the method Iíve chosen to evaluate teams for their degree of balance is one that looks at the individuals playing at least 20 minutes per team game (i.e., 1640 in the season) and their distribution of possessions. For each of those players meeting the time requirement, I calculate a standard deviation of their percentage of possessions used, with that standard deviation centered around an average value of 20%. That Dallas team, for instance, had an "Individuality Measure" of 0.020. It implies that the top guys deviated from 20% of team possessions by only about 2% per man, quite small. The Philadelphia Iversons had an individuality measure of 0.076 and the Minnesota "team" had an individuality measure of 0.082, so each teamís players deviated from 20% possession use by about 8%. These numbers seem to capture the subjective perception of individuality pretty well and have an objective side to them that is logical, allowing the analysis of the NBA through time. It is this individuality measure that forms the basis for the analysis of what has happened in the NBA over the last 25 years. Trends in Individuality Individual possession rates are available back to the 1977-78 NBA season. The league has changed a lot since then, with the addition of the three-point shot and zone defense, the coming and going of numerous Top 50 players, the fast break disappearing, the players bulking up, the game getting more physical, and numerous expansion franchises appearing. With most of these changes, however, Figure 1 shows pretty steady individuality until the 1990ís. Individuality fluctuated around 0.04 until the 1991-92 season when it took a very sudden dip (related to teams giving up simultaneously on no-scoring big guys like Felton Spencer, Jon Koncak, and Larry Smith). Since then, it has been rising steadily. For the last four seasons, league-wide individuality has been closer to 0.05 than 0.04, something that never happened until 1997. Since 1995, at least 55% of the NBA teams every year have had individuality measures of 0.04 or greater; prior to 1995, only one season had 55% of teams at this level. Teams that are highly individualized (greater than 0.06) have made up at least 14% of the NBA (roughly 4 teams) since 2000. Prior to the 1999-2000 season, it was typical to have one or two highly individualized teams.

Something has happened. Part of this is definitely expansion. In years where the NBA has added two expansion teams, individuality has gone up league-wide (it didnít go up with the single addition of Dallas in 1980-81). It would make sense for offenses to cluster a bit more around top individuals if their support is suddenly downgraded, even if it is a small downgrade. Slowing the game, which has been a steady trend for more than 25 years, may also have something to do with individuality, though cause and effect are not clear. You can look at it as:

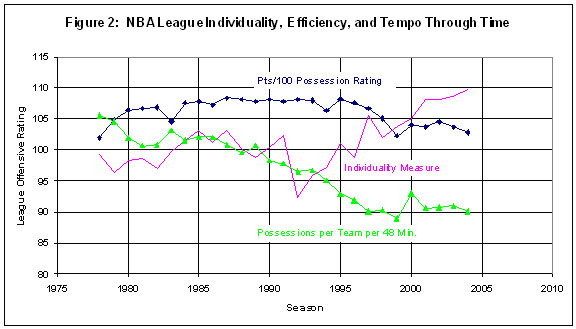

Figure 2 combines some of these ideas into a plot showing the NBA points per 100 possession rating, the average tempo for NBA teams, and the individuality measure. There are two clear suggestions here:

Having put measurements to this, I donít think these conclusions are terribly surprising. Itís essentially what people have been commenting on through the media for a few years, just using a different set of words and something a bit more concrete than general observations. That being said, the league has done things to actually correct this trend. The rule change to permit zone defenses was made to allow more team-oriented and less individual offenses. If you look at that chart, it doesnít look like theyíve taken hold. Despite the dip in efficiency since the rule change, there are actually indications that things are changing. One example is the aforementioned Dallas team. That team was tremendously balanced and a historic great on the offensive end. The Mavericks and the Sacramento Kings, another balanced offense, have been among the league best offenses for several years. With the Mavericks losing several of their best offensive players, they will likely become more individualized around Dirk Nowitzki and fall off quite a lot on the offensive end. Teams like Philadelphia with a lot of possessions being used by one player have seen their offense dry up in the last few years despite more teams going this way. As a bigger summary of these specific examples, the historic correlation between team individuality and offensive rating has been about 18% over 25 years, but in the last four years, it has been reduced to 4%. This reflects that some teams have figured out that balanced is better in this era of zones and have developed great offenses, whereas stubborn teams have resisted, trying to build individual offenses with players who just arenít good enough to be The Man. For more from Dean, see:Basketball On Paper The Olympic Basketball Gap Roboscout looks at the Lakers-Wolves series

|

|

|

Copyright © 2004 by 82games.com, All Rights Reserved